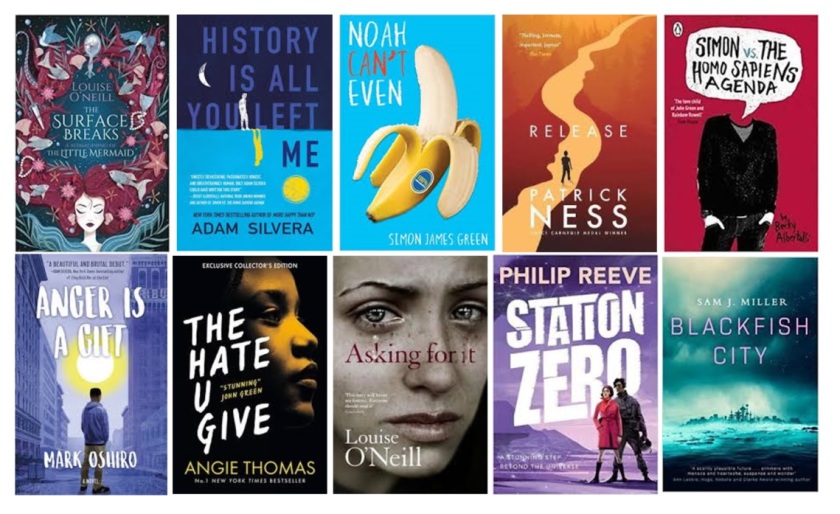

I decided to write a modern fairy tale because of my critical interest in the heteronormative gender binary that is typically presented in classic fairy tales. This is most explicit in the enduring image of the ‘Disney princess’ awaiting rescue by a handsome prince. In recent years, efforts have been made by Disney to diversify from this cliché, such as 2014’s Maleficent and 2013’s Frozen, where female protagonists are not rescued by men but by themselves or other women. At the same time, I’ve been reading a lot of YA fiction written by gay men for gay male teenagers, an emerging trend that is addressing the lack of diverse voices in YA literature. It occurred to me that I could bring the two genres together – fairy tale and gay YA – in a progressive fairy tale with a gay twist, and so I decided to write a modern version of the classic fairy tale, Beauty and the Beast.

While fairy tales maintain an aura of classicism (Zipes, p11), they are in fact constantly evolving and in each evolution the author applies their own moral paintbrush based on the social mores of the time (Tatar, p4). I decided on a structural focus and took the structural elements from Beauty and the Beast by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in Maria Tatar’s The Classic Fairy Tales (1999), the reference for all modern Anglo-Saxon versions of this tale (Tatar, p27). Set in a school that stands in for the Beast’s castle, Tie as Beauty is forced into a partnership with Adam as the Beast. There is a rejection and a reconciliation that corresponds to Tie accepting his feelings for Adam, in parallel to Beauty’s classic acceptance of the Beast as her partner after having left him to tend to her sick father. I wanted to co-opt the happy ending that is traditionally associated with heterosexual couples for a homosexual couple.

Traditionally, animal bridegroom stories like Beauty and the Beast boil down to the female character, at first repulsed by the male Beast character, eventually finding the Beast attractive, at which point he reveals himself as a beautiful human and a perfect match. Theorists have posited that this represents the moment of sexual maturation, where the female character matures enough to not fear sex and allows herself to find the Beast (i.e. the male) attractive. Bruno Bettelheim writes that “to achieve a happy union … the female … has to overcome her view of sex as loathsome and animal-like” (p285). This is problematic because it implies that any rejection of the Beast is down to a lack of sexual maturity and that in the event of correct sexual development the Beast would be accepted, despite appearing Beastly. I wanted to challenge the idea that young people are flowers waiting to bloom in a particular way, and that accepting male sexuality in a heteronormative context is always the right way to develop, in accordance with mainstream society’s expectations. I took my inspiration from Angela Carter’s “The Tiger’s Bride” (1993), where Carter reclaims female sexuality by having her Beauty adopt an animal form rather than her Beast returning to human form. In this context, conflating the moment of sexual maturation with the acceptance of one’s sexuality rather than submission to patriarchal heterosexuality is a radical act.

Feedback I received in my tutorial was instrumental in deciding to deconstruct the characters of Beauty and the Beast rather than simply emulate them with two boys instead of a boy and a girl. I wanted to make Tie, who starts off as fairly obliging and is lumped into a partnership he doesn’t really want, into a sort of mean character. I wanted to portray his demeanour this way partly because there’s a side of him he is refusing to acknowledge that stresses him but also because no one is perfect and I think it’s important for young readers to see that. He’s mean to Adam, who represents the Beast, and that’s not something we would expect of Beauty. After all, Beauty is the very image of virtuousness and kindness (Tatar, p26), but she’s also a patriarchal ideal, which Tie breaks away from. Adam as the Beast is much less of a controlling character than the classic Beast, and he’s quite an emotionally sensitive and reserved character. The question I originally wanted to explore was: what would a modern gay Beauty and the Beast look like? I then asked myself: can I deconstruct the characters of Beauty and the Beast to refresh a tale that is already as old as time? My intention, as reflected in the title, was to blur the lines of traditional gender boundaries to reflect modern reality rather than stick to stock character tropes. As such, the characters of Adam and Tie do not sit comfortably on the outlines of Beauty and the Beast, because the latter are after all ciphers for what Leprince de Beaumont, operating under strictly dictated social conditions, would have considered proper roles for boys and girls to adopt.[1]

This style of the piece – in first person with straightforward language, a near-total absence of metaphor or metonymy that would seem unnatural in a teenager’s internal or external dialogue – takes its inspiration from authors such as Adam Silvera and David Levithan. I find the first person to be fresh and direct, yet it also affords the writer an interesting way of playing with the unreliability of the narrator. For example, in this piece, it’s obvious to Bella that Tie has feelings for Adam, but it hasn’t been so explicitly revealed by Tie himself to the reader because he is not addressing those thoughts – by that stage, the reader will hopefully have figured it out, but if not Bella makes it explicit (p10).

A key scene in this piece that I particularly like partly because of its incongruity is the masturbation scene, because hopefully that shows an animal side to Tie, the character who ostensibly represents Beauty. What I wanted to do was take a character who is supposed to be ‘good’, since Beauty represents perfect feminine goodness, and juxtapose that ideal with a very ordinary yet still taboo act. I also wanted to celebrate that act by making it visible because it’s something that tends to be stigmatised yet is very much part of the fabric of reality, and I also wanted to use it to specifically address Tie’s repression or wilful ignorance of his burgeoning sexuality in the dismissive way the scene ends. It’s quite a sparse scene because I wanted to avoid verbalising, to show rather than tell, and also to imply that Tie actively avoids thinking too much about what he’s doing or done. This is important because Beauty, acting as a cipher for propriety, parrots the morals that Leprince de Beaumont provides for her. The reader never hears Beauty’s own thoughts, only her moralising reasoning. Beauty sacrifices herself for her father not because she wants to but because it is the right thing to do according to her moral education. This is why Tie does not explicitly address his feelings at first –like Beauty, conforming is Tie’s priority, until he splinters from Beauty’s path in accepting and acting on his own feelings.

Patrick Ness, whose novel Release (2017) features an interesting parallel fairy tale alongside his protagonist Adam Thorn’s adventures, said in a talk I attended last year that he wrote Release for his teenage self. I’m really emulating that – everything I write (perhaps until I evolve more as a writer) is what I would have liked to have had around when I was growing up. Similarly, Adam Silvera said in a talk I attended last year that he was writing the kinds of stories he writes, including recently-released What If It’s Us (2018) co-authored with Becky Albertalli, so that there will be some kind of legitimate representation of gay teen boy experiences, which, like me, he felt was sorely lacking when he was growing up.

I’d like this piece to be a drop in the fairy tale ocean, knowing that an ocean is nothing more than a collection of drops. To this end, I am indebted to Jack Zipes, whose writing on the cultural and civilising influences of fairy tales in his 1983 book Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion was indispensable in synthesising a fairy tale that civilises the way I want it to. For Zipes, the fairy tale is an “institutionalised discourse … the writers of fairy tales [enter] into a dialogue on values and manners with the folk tale, with contemporary writers of fairy tales, with the prevailing social code, with implicit adult and young readers, and with unimplied audiences” (p10). It is from this position that I will continue to engage in dialogue through the fairy tale form.

[1] The tale first appeared as part of a collection called Magasin des Enfants in 1757, a didactic work aimed at young girls with the intention of providing moral guidance to the readers (Tatar, p27).

Works Cited

Albertalli, A. and A. Silvera. What If It’s Us. USA: Simon and Schuster, 2018.

Bettelheim, B. The Uses of Enchantment. Great Britain: Penguin, 1991.

Carter, A. ‘The Tiger’s Bride’. The Bloody Chamber. New York: Penguin, 1993.

Ness, P. Release. London: Walker Books, 2017.

Nikolajeva, M. ‘Fairy Tales in Society’s Service’. Marvels and Tales, Vol 16, Num 2. Wayne State University Press, 2002.

Tatar, M. The Classic Fairy Tales. New York: Norton, 1999.

Zipes, J. Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion. New York: Routledge, 1991.

[1] The tale first appeared as part of a collection called Magasin des Enfants in 1757, a didactic work aimed at young girls with the intention of providing moral guidance to the readers (Tatar, p27).

Children's Literature at Cambridge